Our Choices Matter

9/11, Charlie Kirk, and the Evil of Collective Blame

I began writing this post on September 12, 2025. The day before, September 11, was the 24th anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and other targets in the United States.

I remember the day very well, because the fall semester of 2001 was my first semester of full-time college teaching—as a visiting professor of religion at Mount Union College in Alliance, Ohio (years before I found my current position at Marietta College).

I remember announcing the news to the twenty-five or so students, mostly freshmen, at the beginning of a required “Religion and the Human Experience” (RE 100) class. Most had heard the news already. But it was still morning, and there were still many unknowns. Even so, at that point it was clear that the attack was carried out by some group claiming to act in the name of Islam.

I remember asking for a moment of silence to honor the still-uncounted victims. I also remember speaking to students, just before dismissing class early, pleading with them not to blame Islam as religion, or the many millions of peaceful Muslims around the world, including those living in Alliance, Ohio and attending Mount Union College, for the terrible actions of a few who claimed to be representing Islam.

The specter of collective blame particularly concerned me as a religion professor, as it should a college-level teacher of any subject. We academics are charged with teaching and exemplifying critical thinking. To blame all members of a world religion, or any large group of people, for the actions of a few is not only unjust and harmful, it’s illogical.

It’s also ignorant of the facts. Muslims were among the people killed in the attacks on September 11. Muslim organizations across the United States immediately united to publicly condemn the acts of terrorism.

Even my barber, chatting over a haircut less than a week after the event, understood. With no prompting, he opined that to blame all Muslims for the terrorist attacks was “stupid.” Apparently, they teach critical thinking in barber school too.

Amazingly, at least during those first few weeks, the majority of Americans saw things the way my barber did.

To be sure, during that early period there was a wave of retaliation across the country: vandalism of mosques, violent—even deadly—attacks on Muslims, or just people assumed to be Muslim based on their appearance.

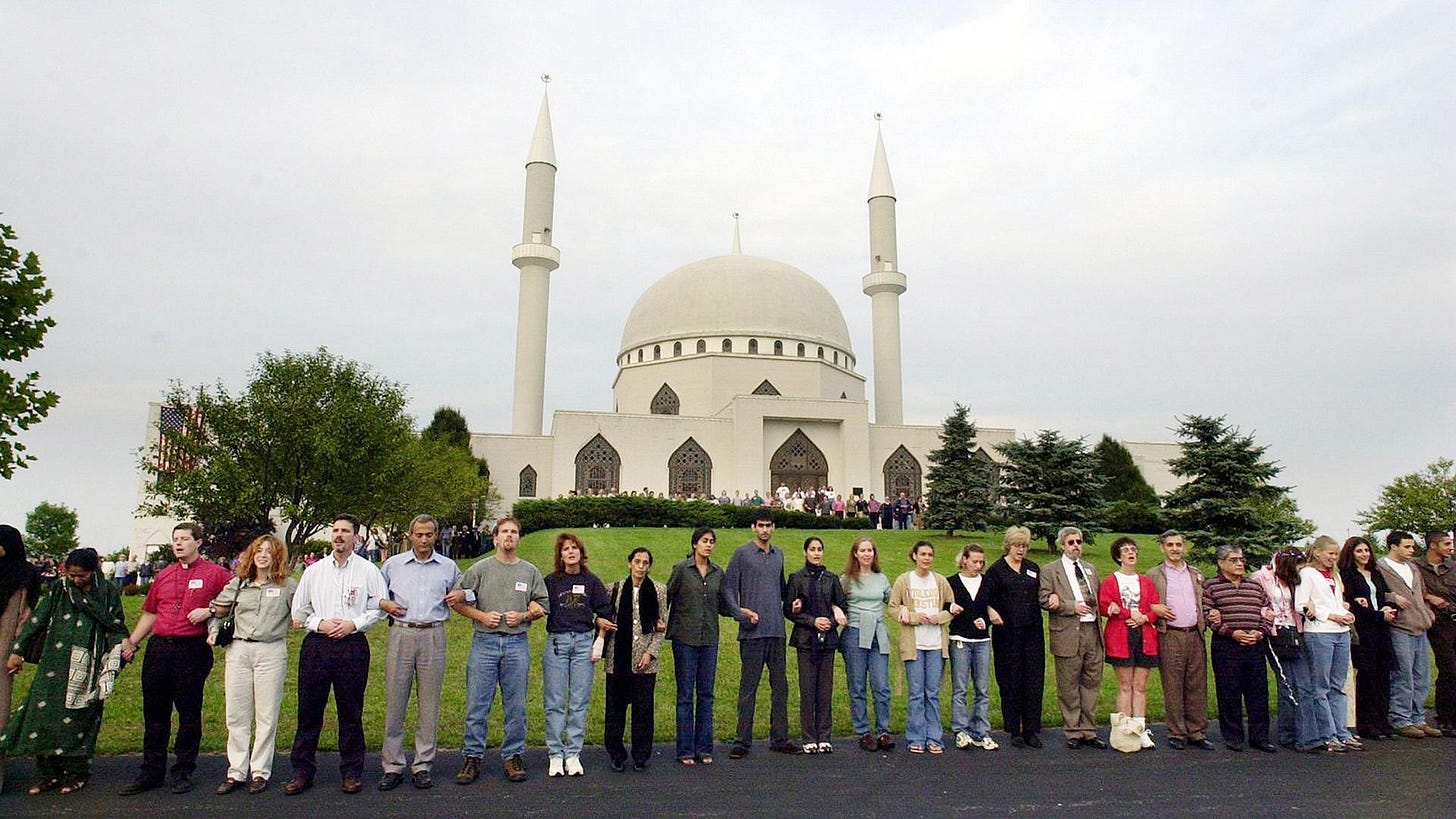

But these retaliatory actions were not characteristic of the attitudes of most Americans. Thousands of non-Muslim Americans reached out to those who were targeted for their faith or their appearance. They reached out to their families and their religious communities. They sent letters, flowers, food, offers of financial support, and offers of protection.

In Toledo, Ohio, over two thousand Christians and others held hands and encircled a mosque that had been damaged by gunfire, praying for the Muslim community that met inside. “Statistically, one would have to say that benevolence outweighed the backlash,” wrote Diana Eck, noted scholar of American religious diversity, in early 2002.

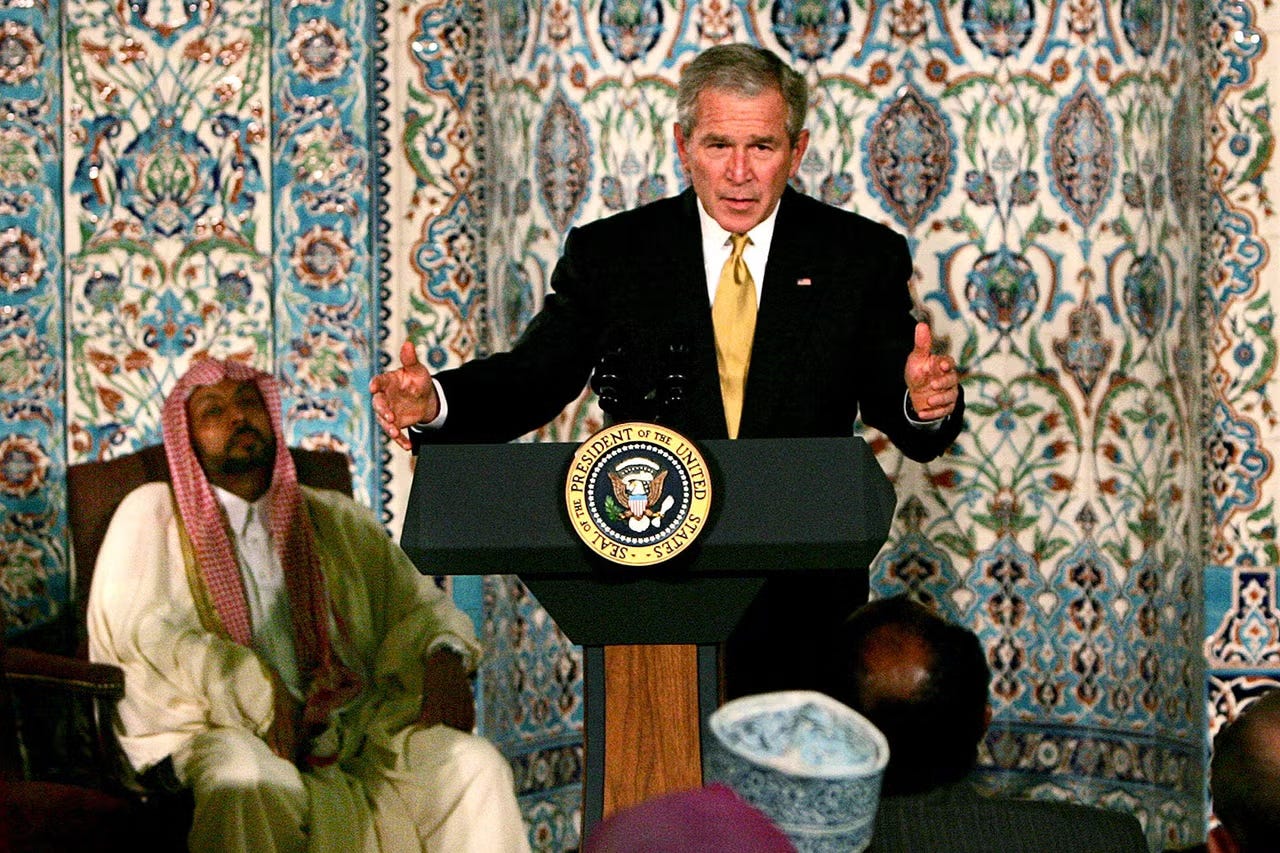

Acts of compassion were accompanied by a growing desire to learn about Islam. Book sales about Islam increased. Muslim speakers were invited to churches and Rotary Club meetings. President George W. Bush encouraged religious tolerance and mutual understanding. Speaking by invitation at the Islamic Center of Washington DC on September 17, 2001, he said “The face of terror is not the true faith of Islam. That's not what Islam is all about. Islam is peace.”

Of course, the moment didn’t last. Hearts hardened. Islamophobic attitudes and actions became more common and more tolerated. “After a brief period immediately following the attacks when Americans expressed an outpouring of support and tolerance for Muslims and Islam, surveys taken since September 11 show that public opinion has grown increasingly negative toward them,” wrote another scholar, Geneive Abdo, in 2006.

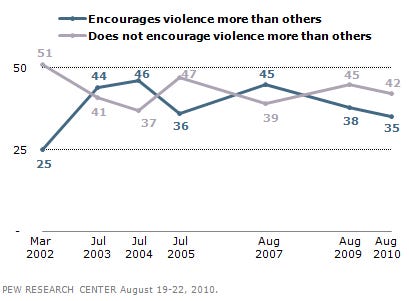

Here is a graphic from one such opinion poll, conducted by the Pew Research Center, tracking American attitudes toward Islam and violence chronologically.

The grey line represents a favorable view of Islam—that Islam does not encourage violence more than other religions. The blue line represents an unfavorable view of Islam—that Islam does encourage violence.

When the chart begins tracking in early 2002, favorable attitudes toward Islam are at their height, and unfavorable attitudes are at their low point. Just over two years later in 2004, the poles have switched. Unfavorable attitudes have peaked and favorable attitudes have reached their nadir.

Many historians have noted the phenomenon of a created cultural memory of a past event, which becomes the commonly accepted narrative for a society, but which differs from the documented facts. I have noticed such a created cultural memory taking hold as I have discussed 9/11 with students over the years, as the event has receded into the past—further away from the current college student’s direct experience.

The popular narrative is that negative American attitudes towards Islam, sadly but inevitably, exploded in the immediate aftermath of September 11, 2001. But negative attitudes inevitably softened over time, to the point that Americans could elect a Black president with a Muslim-sounding Arabic first and middle name in 2008.

The opposite version of this narrative is actually more accurate, based on the Pew data from 2002 to 2004. In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, American attitudes toward Islam were largely favorable, but they became less favorable over time.

However, looking at the whole timeline, from 2002 to 2010, it is most accurate to say that attitudes have fluctuated. And they continued fluctuate to the present day.

What caused these fluctuations? All we can say for certain is that the answers are complicated. Real events, unlike created memories, don’t conform to simple narratives or easy explanations. But even with our limited knowledge, we can affirm this much: our responses to tragedies are not inevitable, forced by huge events that are beyond our control.

It wasn’t 9/11 by itself that drove our attitudes towards Islam. It was 9/11 and a hundred other factors. It was how we as individuals and as a society chose to frame 9/11. It was how leaders, whether in the field of politics, religion, or the media, chose to use their influence to shape public attitudes toward that event, and how we as a public chose to respond to those influences.

In every moment, we can choose how to respond to a tragedy and its aftermath. Sometimes we make good choices, sometimes we make bad choices, but as long as we have any degree of self-awareness, we make choices.

Recently the nation witnessed another violent act. On Wednesday, September 10, conservative activist Charlie Kirk was shot and killed in front of thousands of people while giving a speech at Utah Valley University in Orem.

Again, as I did twenty-four years before, I felt compelled to address this event in an introductory religion class, though it was nowhere near the scale of the tragedy of 9/11. It was on Friday morning, in “Five Big Religions, Five Big Questions” (RELI 101) at Marietta College: our first meeting since the shooting.

I began class by acknowledging the anniversary of September 11, 2001. I told them about speaking to another classroom full of students years ago—acknowledging the evil of the attack, but also warning them against the evil of collective blame.

Then I brought up the shooting of Charlie Kirk. Again, I acknowledged the horror and the injustice of the attack. Because no person deserves to be murdered. No family deserves to be grieved by the violent death of a loved one. No audience deserves to be traumatized by seeing a man shot in the throat in front of them.

People have the right to hold opinions, and advocate for those opinions, without the threat of violence. It doesn’t matter if you think those opinions are wrong or dangerous, or if the person who holds those opinions would not acknowledge your equal rights to free speech and expression. We are obligated to oppose political violence, even against those we disagree with—especially against those we disagree with. The way to oppose speech you disagree with is with more speech, and with advocacy, and with organization, but not with violence.

Then, as I did in 2001, I encouraged the students to exercise critical thinking, and be skeptical of any message that assigns collective blame.

Because even then, less than forty-eight hours after the shooting, before the shooter’s identity, much less the shooter’s political affiliations, were known, the blame was happening. Our country’s leaders, who should know better, were already blaming a vaguely defined “radical left” for the murder, and taking few pains to distinguish this putative “radical left” cabal from just anyone who opposed Charlie Kirk’s politics. That would include a lot of people. Me, for example.

Collective blame is a tempting response to an evil event, because it offers a simple explanation of why evil happens. There are good people and bad people, and the bad people are conspiring to hurt the good people. Such simplistic narratives deny the true complexity and even the free will of human beings. Simplistic narratives have a sense of inevitability about them, a “too-lateness” and “we have no choice” about them.

But the fact is that we do have choices. There are many events that are beyond the power of any one of us to control, but we can always choose how to think about and how to respond to tragic events. We can choose to cast blame and spread fear, or we can choose to reach out to each other and spread love and understanding. In the immediate wake of September 11, 2001, there were Americans who made both kinds of choices, and those choices had consequences.

In the wake of the shooting of Charlie Kirk (and in the wake of another shooting at an ICE facility in Dallas, which occurred during the time it took me to write this essay), we are faced with the same array of choices: to blame or to understand, to hate or to love. If we can learn nothing else from that brief and confusing few weeks after 9/11, it is that our choices matter.

Let’s try not to make stupid ones.

Well done! Thank you.

Thank you! I've shared this with the FUUSM congregtion. I hope they all subscribe! --dawn