Loving Your Enemy

Not a substitute for justice

“Just as a mother would protect the life of her son, her only son, so we should cultivate an unbounded mind towards all beings, and loving kindness towards all the world,” the Buddha told his followers in the Metta Sutta.1

It sounds nice, until you really start trying to do it. It’s easy enough to love “all the world” in the abstract. It’s more difficult to love this or that person, especially if this or that person is your enemy.

Of course, the Buddha was not the only religious figure who told his followers to love their enemies. Jesus also told his disciples (in the Gospel of Matthew), “Love your enemies, and pray for those who persecute you.”

Both Jesus and the Buddha could drop some heavy demands on their followers. And they didn’t always tell their followers exactly how they were supposed to obey them. They left it up to their followers to learn by doing, and to help each other along by sharing their wisdom and experience in religious communities, and to hand down that wisdom and experience through religious tradition.

An important figure in the Buddhist tradition was Buddhaghosa, who lived in the fifth century CE. In his most famous commentary, Visuddhimagga, Buddhaghosa offers his wisdom for how to follow the Buddha’s directives in the Metta Sutta—how to cultivate loving kindness, even for one’s enemies.2

For Buddhaghosa, love of enemies is not an end in itself. It is a step along the way towards attaining a state of loving kindness for all beings. Furthermore, Buddhaghosa admonishes, love of enemies should never be the first step on that journey. It is too difficult a starting point.

Before one can even begin to cultivate loving kindness for an enemy, or any other person, even a friend, one has to cultivate loving kindness for one’s self. Jesus (quoting Torah) tells his followers to love their neighbors as themselves. What good does it do our neighbor if we don’t really love ourselves? We need to know what happiness is for ourselves before we can wish it for others.

So, how does one cultivate loving kindness for oneself? By practicing Buddhaghosa’s famous Metta meditation.

Take a deep breath and repeat, “May I be filled with loving kindness. May I be safe from inner and outer dangers. May I be well in body and mind. May I be at ease and happy.”

Then take another deep breath, then repeat the saying, and repeat it again, with each breath, until you really mean it.

Then, when you truly desire those good things for yourself, you can move towards directing those good thoughts toward another person. Repeat the saying, but replace the “I” with the name of a venerated teacher, and then with the name of a beloved friend.

When you have reached the point of desiring the happiness of each beloved person as much as you desire your own happiness, then you can move on to the next, slightly more difficult step. Replace the name of the beloved person with the name of a neutral person, someone you don’t have strong negative or positive feelings about. Repeat until you have the same compassion towards the neutral person that you would towards your beloved friend.

Then, after completing this baby step, you can take the next, more challenging, one. Repeat the saying again, but this time replace the name of the neutral person with the name of a hostile person, an enemy. Repeat the meditation until you regard your enemy, if not yet as a beloved friend, then at least as you would a neutral person.

“What if I don’t have any enemies?” you might ask. Buddhaghosa acknowledges there are some people who are so enlightened that they don’t feel animosity toward anyone. To them, Buddhaghosa says (more or less), “Good for you.”

Most of us, though, have someone who makes us cringe whenever we think of them, often for good reason—because that person has harmed us or people we care about. Buddhaghosa tells us, not only to think about that person, but to repeatedly wish for that person love, kindness, safety, health, and happiness. Only when we have cultivated genuine loving kindness for the enemy can we move on to the final step of directing our compassion to all sentient beings.

Buddhaghosa knows how difficult this penultimate step is. That is why he offers his audience a lot of help. First, Buddhaghosa suggests meditating on the dangers of harboring resentment. Resentment makes one “a prey to anger, ruled by anger,” which does one no good, even if that anger is justified. Suppose someone “provokes you with some odious act.” Buddhaghosa explains, “If you get angry, then maybe you make him suffer, maybe not; though with the hurt that anger brings, you are certainly punished now.”

If, even after meditating on all the spiritual dangers of resentment, one still harbors resentment towards one’s enemy, Buddhaghosa suggests another path. Remember and reflect on some good quality the enemy has shown. Think of some instance in which the enemy has demonstrated self-control—of their bodily actions, of their speech, or of their thoughts—for the sake of others.

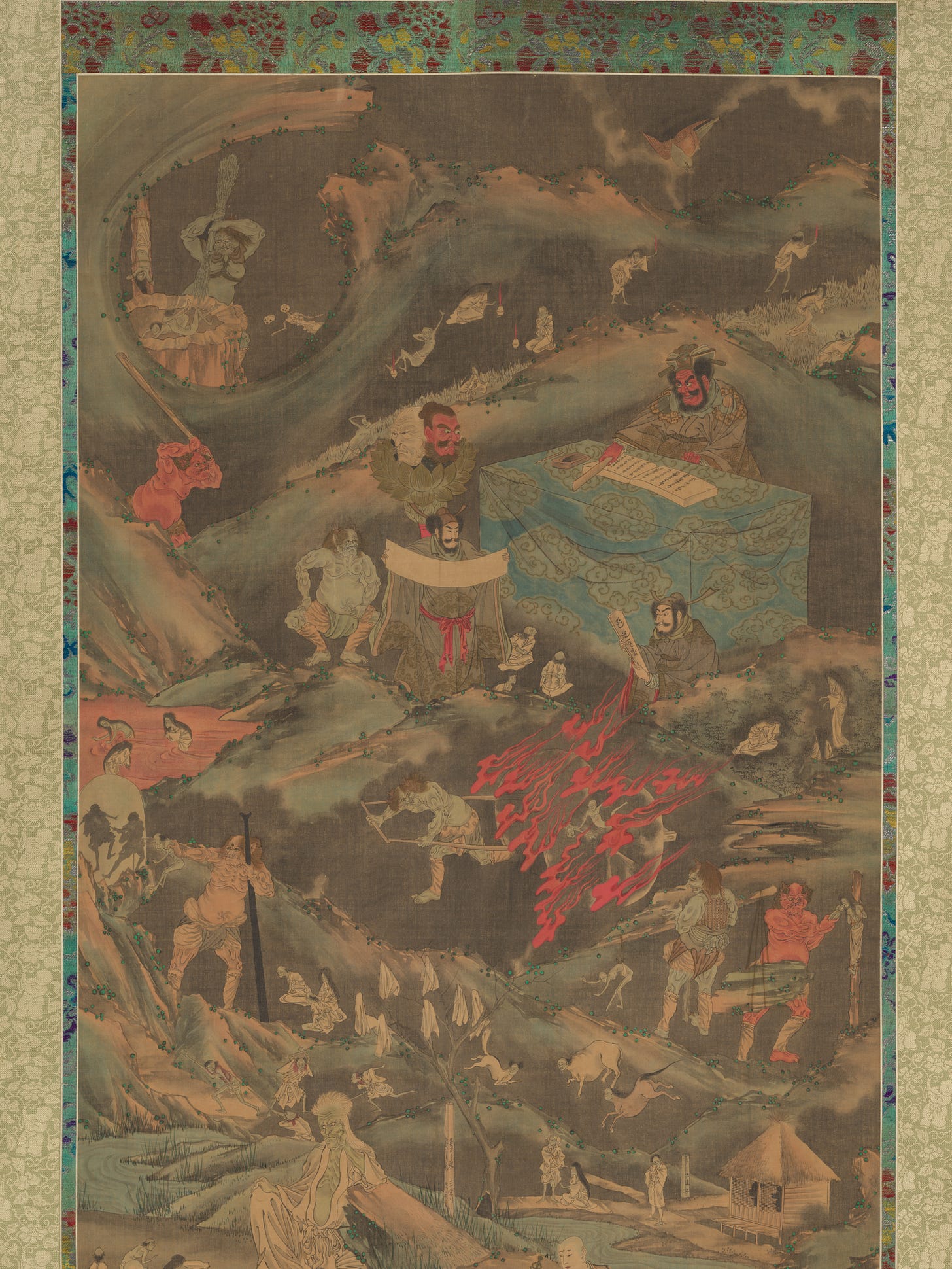

If nothing comes to mind—if the enemy has truly demonstrated no ability to keep his hands to himself, or to refrain from hateful speech, or to overcome hateful or bigoted beliefs, then one should have even more compassion, because that person is acquiring terrible karma, and will soon “find himself in one of the eight great hells or the sixteen prominent hells.”

Many students who sign up for my Buddhism class are drawn to it because they think Buddhism contains less judgment, punishment, and hell than the religions they were brought up in. They are right about the judgment and punishment parts. Buddhism does not center on a personal divine being who makes moral judgments and doles out rewards, punishments, or even forgiveness to people. Karma is simply the outworking of our own actions. No one imposes karma on us, a Buddhist would say, we create our karma for ourselves.

On the other hand, there is plenty of hell in Buddhism. Quantitatively there is more hell (or rather, more hells) in Buddhism than in Christianity, at least 24 times as many, according to Buddhaghosa. True, Buddhist hells are not eternal. They are where beings work out bad karma before being reborn as another being on another plane. But a term in a Buddhist hell can last for eons, and an eon is…a very long time. Furthermore, Buddhist texts describe the sufferings of beings in the various hells in ghastly detail, more vividly than any description of hell in the New Testament.

Hell is a hot topic, so to speak, and not a rabbit hole (or hell hole?), I intended to dive into in this Substack. But Buddhaghosa’s reference to the consequences of evil actions raises an important point and corrects a potential misunderstanding.

Neither in Buddhism nor in Christianity is love of enemies supposed to be a substitute for justice. True love of enemies does not separate people from the consequences of their actions. It is not permission to let someone walk all over you. Love of enemies is not (as some critics of nonviolent social action call it) knuckling under to oppression.

Loving my enemy is both free and freeing. Free, because love by definition cannot be compelled, and freeing, because loving my enemy frees me from the burden of resentment. It is also freeing for my enemy.

To love another person is to have that person’s best interests at heart. It is to wish for that person what one would wish for one’s self. I want to be free from the power of sin (to use the Christian language) or selfish desire (to use the Buddhist language) that can cause me to harm others. I should want the same freedom for another person, whether that person is my friend or my enemy.

To restrain a person’s harmful actions, and to make that person take responsibility for those actions, need not be acts of revenge. They can be acts of love that can lead an estranged enemy to redemption and to reconciliation with others.

So, when I say the Metta meditation on behalf of my enemy (whoever that may be)—when I wish love, kindness, safety, health, and happiness for my enemy—when I repeat those wishes over and over until I truly mean them—I am doing so with the hope that both my enemy and I will attain higher levels of compassion.

I am not saying that my enemy’s bad behavior should be permitted or encouraged, or that he should not be held accountable for his actions, or that he should be given power to harm others irresponsibly, or that he has any business being president of the United States!

Oops. Do I need to start over?

Translated from Pali by by K.R. Norman, in Norton Anthology of World Religions: Buddhism, edited by Donald S. Lopez, Jr. (2005).

Translated from Pali by Bhikku Ñāṇamoli, in Norton Anthology of World Religions: Buddhism, edited by Donald S. Lopez, Jr. (2005).

nice article!

Thank you, Dr. Torbett. This arrived in my in-box with perfect timing. As always, it is thought provoking - offering insights and knowledge not previously considered or known. This article has already been printed, ready to be annotated, highlighted, and left where it can frequently be re-read.